Multidimensional Impacts of Mobility on Health

Anant Jani (06 October 2024)

This piece was initially presented at a workshop held by the Wellcome Centre for Cultures and Environments of Health at the University of Exeter (hybrid) on 4-5 July 2024. It was supported by Wellcome Trust Centre Grant [203109/Z/16/Z] and explored “Everyday Mobilities: Social, Cultural, and Environmental Perspectives on Getting Around.” (You can see event recordings here - day 1; day 2.). In recent years, daily travel - especially in urban spaces - has been increasingly politicised. Concerns about the climate emergency, air pollution, and inequities of health and risk exposures have shifted discussions about everyday mobility, simultaneously producing new policy thinking, planning experiments, activist movements, and public backlash. This workshop explored these developments, examining the social relations, cultural frames, and environmental concerns with which everyday travel has become entangled in different local, national, and transnational contexts, as well as attending to the varied histories and possible futures of "getting around”. The "Everyday Mobilities” series on M&M is a first step towards the establishment of an Everyday Mobilities interdisciplinary network bringing together scholars, practitioners and campaigners.

Dr. Anant Jani is an Oxford Martin Fellow at the Oxford Martin School, University of Oxford. He currently works on understanding how we can improve population health through social prescriptions and by addressing social determinants of health. Prior to his position at the University of Oxford, Anant worked in Europe and the Middle East to help healthcare systems within these countries to focus more on value-based healthcare. Dr. Jani has a PhD in immunology from Yale University.

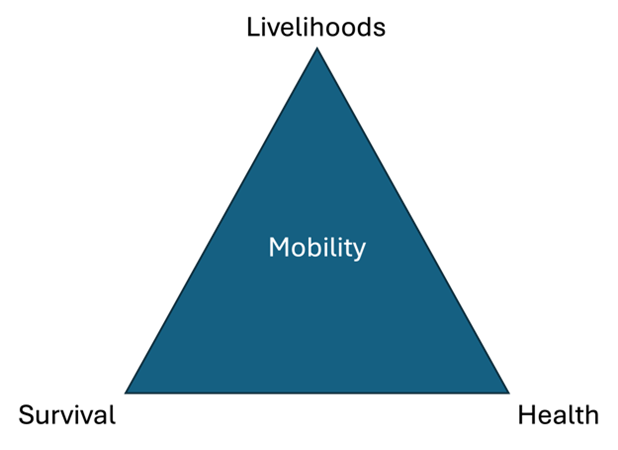

There is often a misguided view that health is mostly delivered through healthcare professionals, GP surgeries, hospitals, diagnostics, and/or pharmaceuticals. While these factors are important, they are necessary but not sufficient to deliver health. The reality is that 70-80% of health outcomes are directly linked to determinants of health (social, environmental, commercial, digital, political) that dictate the opportunities people have to engage in activities that promote health and prevent disease. Determinants of health include housing, education, employment, diet, physical activity, clean air, clean water, and access to transport. Though one might be inclined to batch ‘mobility’ directly with access to transport, a bit of exploration reveals that mobility is a critical factor to delivering health across multiple dimensions including livelihoods, health and survival:

Livelihoods

Mobility is necessary for people’s livelihoods. Those who are employed need to be mobile to access their employment, whether that be through active transport (e.g. walking, cycling), public transportation (e.g. trains, buses), or automobility (e.g. motorbikes, cars). They also need to be mobile to do their work – even for people who are office based, some level of mobility is necessary for them to carry out their employment related activities.

An important consideration on mobility is linked to inequalities linked to access. If we start with physically getting to work, there is a significant amount of variation in the resources (both money and time) required by different population subgroups to get to work. For example, while the average London worker needs to work for 44 minutes/day to pay for their daily commute, those earning less (£599/month or less) need to work for 54-116 minutes to pay for their daily commute. There is a significant negative externality and opportunity cost linked to this unequal access to affordable mobility both from the financial (i.e. they could have used this money for other things that could contribute to their health/wellbeing like more nutritious food) and time (i.e. those needing to work more to make ends meet or those needing to commute longer distances could have used that time to engage in leisure or social activities with their family or friends).

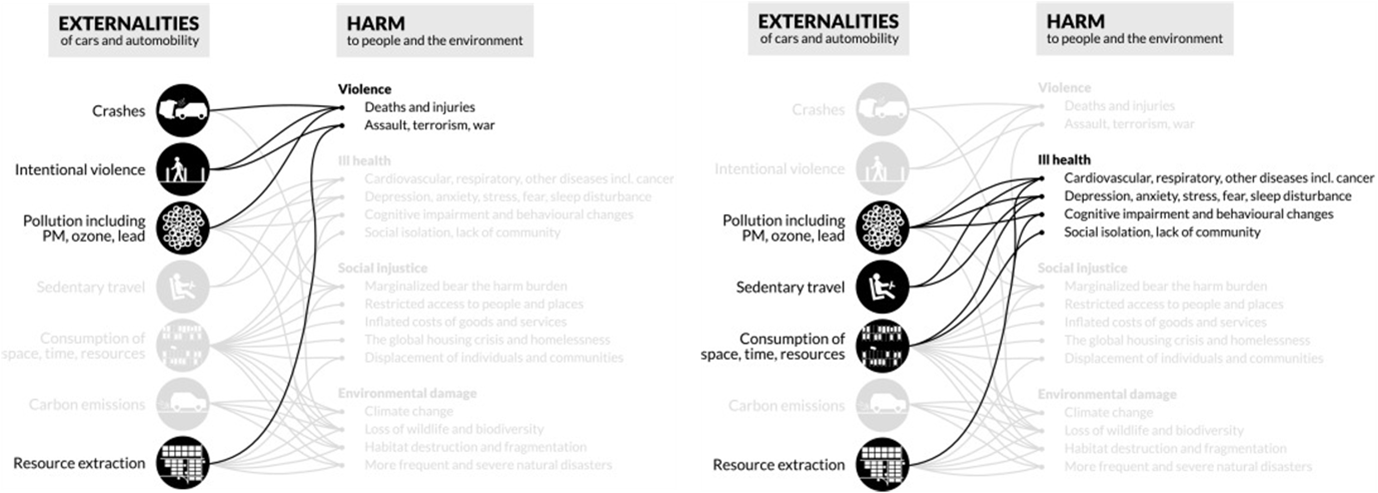

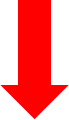

There are also direct and indirect negative impacts on health. For example, longer commutes that rely on modalities that do not include active transport, increase the amount of time a person is sedentary (see section below on health), which increases a person’s risk for cardiovascular related ill health. Additionally, automobility as a means of mobility has several negative externalities that can be attributed to it linked to violence and ill health:

Since their inception, it is estimated that cars and automobility have killed between 60-80 million people – approximately 1 in 34 deaths.

Health

Mobility has a direct link to health through physical activity. As highlighted in the section above, mobility related to people going to their places of employment could result in physical inactivity if people use modalities of transportation that are not active (e.g. walking, cycling). But lack of mobility linked to more general physical inactivity is even more problematic with social and environmental risk factors manifesting as socially driven physical inactivity and disablement. Much of this is associated with increased car ownership/driving, the transition from manual labour to desk-based work and the increase in leisure activities where people are more stationary/sedentary (e.g. surfing the internet, video games, binging on Netflix).

Combined with poor diets, physical inactivity is directly linked to the increased incidence and prevalence of preventable health conditions (non-communicable diseases – NCDs) such as high blood pressure, high cholesterol, type 2 diabetes, overweight/obesity, and cardiovascular disease. In Europe, NCDs account for 75% of all diseases and 85% of all deaths. The financial implications are equally as dire, with European healthcare systems spending about €700 billion annually to treat NCDs, which accounts for about 70% of the total amount spent on healthcare Projecting forward, it is estimated that 51% of the global population will be overweight or obese by 2035, which could lead to an economic impact of about $4.32 trillion annually.

Survival

Improved living standards and healthcare since World War II have manifested in substantial increases in life expectancy globally. Since the 1950s life expectancy has increased by more than 10 years in Europe, North America and Oceania; about 25 years in Latin America and the Caribbean; and about 30 years in Asia. If current trends continue, it is estimated that we will see a doubling in the number of people 60+ by 2050 to nearly 2 billion people.

Population ageing is poised to become one of the most significant social transformations of the twenty-first century, with implications for nearly all sectors of society, including labour and financial markets, the demand for goods and services, such as housing, transportation and social protection, as well as family structures and intergenerational ties.

While biological and social factors dictate the ageing process, it is important to note that ageing is not a linear process. As highlighted in the preceding section, socially-driven disablement and inactivity has a direct impact on health and when this accumulates over decades of a person’s life, in addition to contributing to NCDs, it can also lead to loss of fitness, reduced resilience (i.e. ability to cope with life’s changing circumstances), decreased autonomy, and increased chances of dependency.

In the context of ageing, there are two key broad groups of activities that people need to be able to engage in to cope with life’s changing circumstances – activities of daily living (ADLs) and instrumental activities of daily living (IADLs). ADLs consist of activities like ambulating (walking, sitting, standing, lying down, getting up, going up the stairs), grooming, getting to the toilet, dressing, and eating. IADLs consist of activities like managing one’s finances, looking after oneself and others, shopping, doing chores, preparing meals, managing transport, and engaging in hobbies. When people are not able to independently carry out ADLs and/or IADLs, their dependency will increase and this could lead to a negative cascade of decompensation that will ultimately mean that they lose their independence. This trend is, unfortunately, manifesting in some stark ways in our ageing societies. In the UK, disability in those under 18 is about 5.8% and increases to 44.6% in those aged 65-74 and to a stark 84.2% in those over 85 years of age. These trends are also seen for people requiring help with ADLs or IADLs with 21% of people aged 65-69 needing support and 52% of those 80 and over needing help with the same activities. Furthermore, those who are 65+ and are the most deprived subgroups of the population have a two-fold increased likelihood of needing help with ADLs or IADLs as compared to their less deprived cohorts .

Socially-driven inactivity and dis-ablement

Loss of ability due to loss of fitness (fitness gap)

Reduced resilience & autonomy

Increased chances of dependency

Conclusion

There is a complex interplay between mobility, health, and disease through multiple, interlinked dimensions linked to livelihoods, health, and survival.

In some instances, mobility ties to a determinant like employment, but the nuances around the type of transport taken (e.g. cars vs. active travel) can determine whether the modality of mobility used will lead to short to long term health or disease for the individual themselves as well as others around them. Or to put it another way, mobility across its multiple dimensions leads to various externalities – both positive and negative. Further to this, different modalities of mobility can have various opportunity costs that sometimes require tough trade-off decisions. For example, while active travel is better for your health, in some cases it can also take longer. An extra minute spent on active travel is one less minute one can spend on cooking, spending time with loved ones, or spending time on leisure activities.

The externalities and opportunity costs linked to mobility means that decisions around policy and practice are not straightforward. It would be simplistic to say that everyone should engage in active travel without considering the costs (money and time) of active travel. For example, are the tax incentives and purchase premiums for cycling a good use of tax payer money and do they yield the environmental and health benefits that they are expected to deliver? Is the “Vienna Model” of providing subsidised access to public transport effective in delivering benefits to citizens and society? Going forward, furthering our nuanced understanding of mobility can help us to better understand the barriers and facilitators of using mobility to promote health and prevent disease. This can then directly inform how we design, implement and evaluate policies that provide equitable opportunities for people to utilise mobility in a way that positively impacts livelihoods, health and survival.